Really Useful Engines

Continued from Part 1:

- The Grammar of Entropy

- Algorithmic Information Theories of Life

- The Mathematics of Efficiency

- Universal Really Useful Engines

- Compossibility: The Thermodynamic Case for Diversity

- Footnotes

The Grammar of Entropy

“But entropy, heat, past and future are qualities that belong not to the fundamental grammar of the world but to our superficial observation of it. ‘If I observe the microscopic state of things,’ writes Rovelli, ‘then the difference between past and future vanishes … in the elementary grammar of things, there is no distinction between “cause” and “effect””1

Whilst we must be very careful to avoid bringing this tricksy second law into potentially subjective definitions of order and structure, in respect of doing useful work and creating the conditions for greater freedom of action we should be on somewhat safer ground.2

By living and evolving through variation, life-forms create useful information and this gives rise to other complex life-forms. This is the simplest summary of how all life-forms on Earth evolved from a simple shared ancestor. All DNA-based life-forms3 on Earth show this evolution (variation) from simplicity in code in having a common DNA sequence (coding for rRNA):4

GTGCCAGCAGCCGCGGTAATTCCAGCTCCAATAGCGTATATTAAAGTTGCTGCAGTTAAAAAG

Entropy, like evolution, is unusual in not being an equality. This also tells us something fundamental about the nature of nature. Natural evolution (as a life process on Earth) and entropy are strongly twinned together.5 When James Lovelock (proponent of the Gaia theory)6 was asked how he would look for life on Mars, he replied:

“I’d look for an entropy reduction, since this must be a general characteristic of life.”7

(James Lovelock)

The simple, non-contentious view, first put forward over 100 years ago, is that life-forms are the most extraordinary known natural useful engines in the universe.

“Thus a living organism continually increases its entropy – or, as you may say, produces positive entropy – and thus tends to approach the dangerous state of maximum entropy, which is of death. It can only keep aloof from it, i.e. alive, by continually drawing from its environment negative entropy – which is something very positive as we shall immediately see.”8

(Erwin Schrödinger)

As such, life always has some potentially measurable impact on its environment and some value, even using a strictly utilitarian approach for all living things (whether sapient, sentient or otherwise). It may be that our understanding of entropy is still nascent and, given the equivalence of matter and energy by E = mc2, the differences between the entropy of matter in an expanding, ‘cooling’ universe is cancelled out eventually by a decrease in gravitational entropy of the whole system as it collapses or gravity ceases to apply (there being no matter with which to bend space-time and conceptualise any space between things). Perhaps material and energy entropy are just the two faces of an underlying unity. They may always sum to zero entropy again when all matter and energy recombine – such as at a singularity, whether at the event horizon of each black hole, the pre-Big Bang singularity or at the end of this current universal epoch.9

“Now as I was young and easy under the apple boughs

About the lilting house and happy as the grass was green,

… Nothing I cared, in the lamb white days, that time would take me

Up to the swallow thronged loft by the shadow of my hand,

In the moon that is always rising,

Nor that riding to sleep

I should hear him fly with the high fields

And wake to the farm forever fled from the childless land.

Oh as I was young and easy in the mercy of his means,

Time held me green and dying

Though I sang in my chains like the sea.”10

Algorithmic Information Theories of Life

Life as a Demon: The Cost of Information

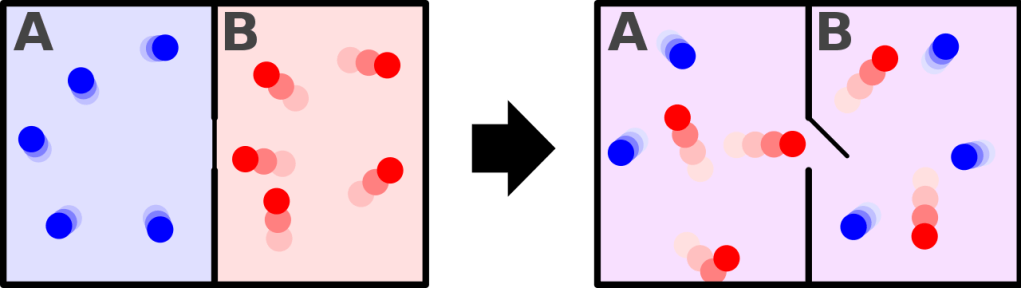

“In the thought experiment, a demon controls a small door between two compartments of gas. As individual gas molecules approach the door, the demon quickly opens and shuts the door so that only fast molecules are passed into one of the chambers, while only slow molecules are passed into the other. Because faster molecules are hotter, the demon’s behaviour causes one chamber to warm up and the other to cool down, thereby decreasing entropy and violating the second law of thermodynamics.”11

To understand how life handles information, we have to look back to a famous 19th-century thought experiment: Maxwell’s Demon. The physicist James Clerk Maxwell imagined a tiny being controlling a door between two gas chambers. By letting fast molecules into one side and slow ones into the other, the demon could create a temperature difference—ordering the gas and apparently violating the second law of thermodynamics.

But there was a catch. Later physicists like Leo Szilárd and Rolf Landauer realized that the demon isn’t magic. To do its job, it has to measure the speed of molecules, store that information, and then act. This process has a thermodynamic cost. There is always an energy or information cost of any agent acting to change any thermodynamic system, wiping the demon’s memory to make room for new data generates heat.

In recent years, physicists have built real-world Maxwell’s demons using superconducting quantum circuits. In these experiments, a ‘demon’ (a microwave cavity) measures the state of a qubit and uses that information to extract work in the form of photons. These experiments have experimentally verified the information-to-work conversion, demonstrating that information is not an abstract concept but a physical feature that can help drive a system, provided one pays the cost of erasing the memory afterward.

Life-forms are these work demons. We gather immense amounts of information to solve the problems of survival. But because information costs energy, life is under extreme pressure to be efficient. We, or it, cannot afford to be wasteful with calculations.

The Algorithm of Survival

“Living entities, especially the ones we are familiar with, like a horse or an olive tree, can be thought of as replicating objects in space that have gathered, over considerable evolutionary time, immense amounts of information on how to solve a multitude of problems they might face in their lifetime.”12

(Ioannis Tamvakis)

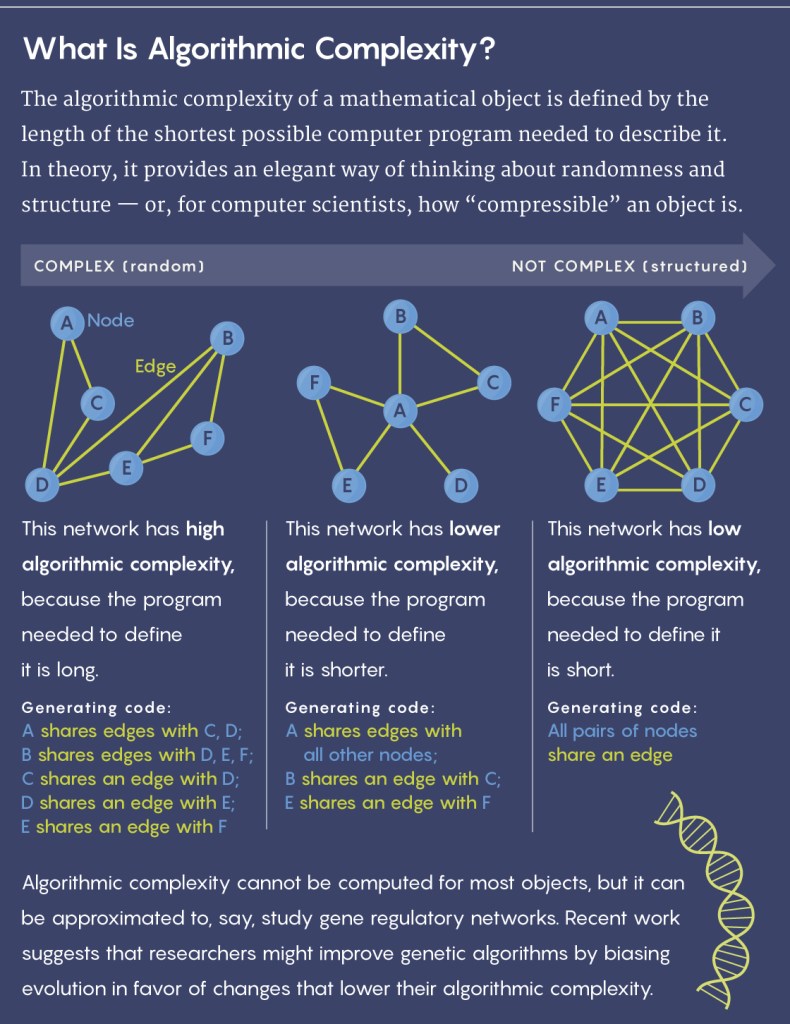

This pressure for efficiency drives life toward what mathematicians call Algorithmic Information Theory (AIT). In this framework, the complexity of an object is defined by the length of the shortest computer program needed to describe it.

Nature loves short code. A random string of numbers is “complex” because you have to list every single digit to describe it. But a structured object—like a snowflake or a protein—can be described by a much shorter algorithm.

Life has mastered this algorithmic compression. Evolution doesn’t just store data; it finds shortcuts. It encodes the useful knowledge of billions of years of survival into compact genetic sequences. This is why biological systems are astoundingly efficient—beating our best supercomputers by orders of magnitude when it comes to the energy cost of processing data.

Coding for Diversity

This is not a random walk; it is a calculated one. As Gregory Chaitin suggests, evolution navigates “software space,” discarding inefficient code and optimising for solutions that work.

“evolution can be understood as a kind of random computational walk through software space.”13

(Gregory Chaitin)

This perspective fundamentally changes how we view our own biology. We are not just matter; we are “writ in letters – GATC”. Our DNA is a record of successful computations, a history of problems solved and efficiency gained. And just as a good programmer avoids bloat, nature avoids waste, using “fractal” efficiency to build complex organisms from simple, repeating instructions.

“A genome, then, is at least in part a record of the useful knowledge that has enabled an organism’s ancestors – right back to the distant past – to survive on our planet … Looked at this way, life can be considered as a computation that aims to optimize the storage and use of meaningful information. And life turns out to be extremely good at it.””14

(Philip Ball)

We are engines that of compress the chaos of existence into a story that can be made sense of and remembered to survive.

The line or leap between pre-organic matter to aliveness may be something that we should expect to be replicated elsewhere in the universe, or perhaps it was one incident of inexplicable and improbable good luck. It would be wise for us to act as if it is a case of universal good luck.

Life-Forms Must Be Efficient

The evolution of life-forms has been dictated by the use and development of a number of extraordinary biological algorithms. Life-forms must keep the energy costs of storing and transmitting survival and genesis information to the lowest possible level and as close as possible to the efficiency threshold (known as the ‘Landauer bound’), given the increased costs in energy and entropy of creating and retaining such information.

“the cost of computation in supercomputers is about eight orders of magnitude worse than the Landauer bound … which is about six orders of magnitude less efficient than biological translation when both are compared to the appropriate Landauer bound. Biology is beating our current engineered computational thermodynamic efficiencies by an astonishing degree.”15

Life-forms are demons that direct the flow of energy and matter and try to externalise the costs of staying alive by dumping waste into the surroundings; they can only do this if they develop means of storing, compressing, decoding and discarding information about what is helpful in the struggle for survival and perpetuation. Encoding information in DNA, RNA and in social culture are ways in which life-forms seek to maintain an advantage in this continuous struggle. Organic hardware and biological software is much more efficient than the best supercomputers in doing so.

Living things are engaged in a constant sequence of ‘if-then’ assessments (even if of not fully consciously) to maintain their identity; persistence requires ‘good enough’ predictions about the future. The costs of these continuous calculations and the accumulation of information and errors in the replication of information (including in living cells) eventually lead to individual death – as the most efficient means to continue the perpetuation of life in newer forms.

The Mathematics of Efficiency

AIT is the math of that efficiency—compressing complex data (survival) into short code (DNA)

“A code for generating the first 15,000 digits of pi in the programming language C, for instance, can be as short as 133 characters.”16

(Jordana Cepelewicz)

Algorithmic information theories (AIT) are being used in advanced AI, biotech and other applications to try to use efficient short-cuts to generate useful results. Scientists realise that we need to learn more from the natural systems around us. A simple way of thinking about AIT is to consider that it takes much less information to provide the process (steps or algorithm) to generate π than it does to calculate it.

“Creationists love to insist that evolution had to assemble upward of 300 amino acids in the right order to create just one medium-size human protein. With 20 possible amino acids to occupy each of those positions, there would seemingly have been more than 20300 possibilities to sift through, a quantity that renders the number of atoms in the observable universe inconsequential … it would have been wildly improbable for evolution to have stumbled onto the correct combination through random mutations within even billions of years. The fatal flaw in their argument is that evolution didn’t just test sequences randomly: The process of natural selection winnowed the field.”17

In the blockchain space, we also see the use of tools that take advantage of algorithmic simplicity to create data complexity – for example, use of elliptic curve digital signature algorithms (ECDSA) to create digital signatures that everyone can validate easily but that are extraordinarily difficult to fake or to use to break the underlying private keys linked to them.

Natural systems (even non-living ones, such as solar systems) tend towards maximum simplicity and stability whilst generating entropy in doing so. This ties in with theories on how unconscious matter is likely to naturally self-organise into life-forms in order to better dissipate environmental energy.

Given the various attractive effects between bodies, smaller bodies such as atoms are also likely to form collective patterns and arrive naturally at more stable energy forms. The transformation of atoms into life-forms is a very efficient way to dissipate free energy. The beautiful appearance of complexity and order seen in fractals is also an example of algorithmic efficiency.

“Life resembles a fractal … The ‘fractals’ of life are cells, arrangements of cells, many-celled organisms, communities of organisms, and ecosystems of communities. Repeated millions of times over thousands of millions of years, the processes of life have led to the wonderful three-dimensional patterns seen in organisms, hives, cities and planetary life as a whole.”18

(Lynn Margulis and Dorion Sagan)

It should not be surprising that living nature has taken advantage of algorithmic simplicity to find short-cuts to survival solutions. The walk may be random, but the work becomes iterative and also gives rise to variations on a theme, when success is chanced upon.

Chaitin contends that the walk and work done by nature and life-forms is not entirely random, instead following a distribution based on Kolmogorov complexity. The Kolmogorov complexity of something is the length of the shortest algorithm or code that produces the result. This gives rise to accelerated evolutionary solutions to problems that are not possible in an entirely random distribution.19 Randomness under this approach is the extent to which any string of data cannot be algorithmically compressed.20

“We argue that the proper framework [for consciousness] is provided by AIT and the concept of algorithmic (Kolmogorov) complexity. AIT brings together information theory (Shannon) and computation theory (Turing) in a unified way and provides a foundation for a powerful probabilistic inference framework (Solomonoff). These three elements, together with Darwinian mechanisms, are crucial to our theory, which places information-driven modeling in agents at its core.”21

(Giulio Ruffini)

The ability of living organisms to think or make decisions arises from the need of life-forms to model changes in the surrounding environment, including the impact of the actions of the life-form itself. Reality is really just the best model each life-form believes in, or works within, to make the simplest sense of their environment given the overwhelming and non-computable quantity of data in everyday life.22

Nature and life (like science and logic) love and reward efficiency. We demand that our theories, axioms and laws are much simpler than the reality they seek to represent since otherwise they are of no use. Such theories are like computer programs on which we can operate algorithms. Indeed, the most ground-breaking theories are often extraordinary in their apparent simplicity (think E = mc²) — they are also a type of algorithmic efficiency.

Life-forms are a process for simplifying and solving complex problems, where the solution has to be worked in reality and the consequences of failure are often final. In addition to the algorithmic efficiency that is needed to work more intelligently (to conserve energy), nature has an in-built drive for maximal diversity.

Diversity is the strategy that best ensures that some life-forms and species (and therefore life itself) always perpetuate. This drive for diversity is most on show after periods of biospheric destruction or catastrophe, as witnessed by the many periods of great speciation in the Earth’s past (including the Cambrian explosion). This requirement of diverse solutions gives rise to the need to coexist—compossibility— it appears to be nature’s ultimate strategy for surviving in an entropic universe.

“Contrary to the tendency of optimization algorithms to converge over time to a single ‘best’ solution, natural evolution instead exhibits a remarkable tendency toward divergence – continually accumulating myriad different ways of being. This observation is the crux of an alternative perspective in evolutionary computation (EC) that has been gaining momentum in recent years: evolution as a machine for diversification rather than optimization.”23

Sapients are therefore required to take account of the utility value of different species (perhaps partly quantified using algorithmic information theory) and the scientific and sacred value of diversity of species in their decision-making or they risk – at best – an avoidably impoverished life and loss of valuable information. Failure to do so may even encourage destruction by others that might inform their ethical frameworks on our current behaviours and laws (such as aliens or AI).

“The invisible Spirit (Atman) is eternal,

and the visible physical body is transitory …

The Spirit by whom this entire universe is pervaded is indestructible.

No one can destroy the imperishable Spirit.

The physical bodies of the eternal, immutable,

and incomprehensible Spirit are perishable.”24

Universal Really Useful Engines

Life is universal energy manifesting in extraordinary utility machines; life-forms are really useful engines.

We do not know how widespread life is or whether it is confined to Earth, though the sheer vastness of the universe25 makes it plausible that life is already experimenting in other parts of the Milky Way or other galaxies. Though, as Enrico Fermi asked: “where is everybody?”26

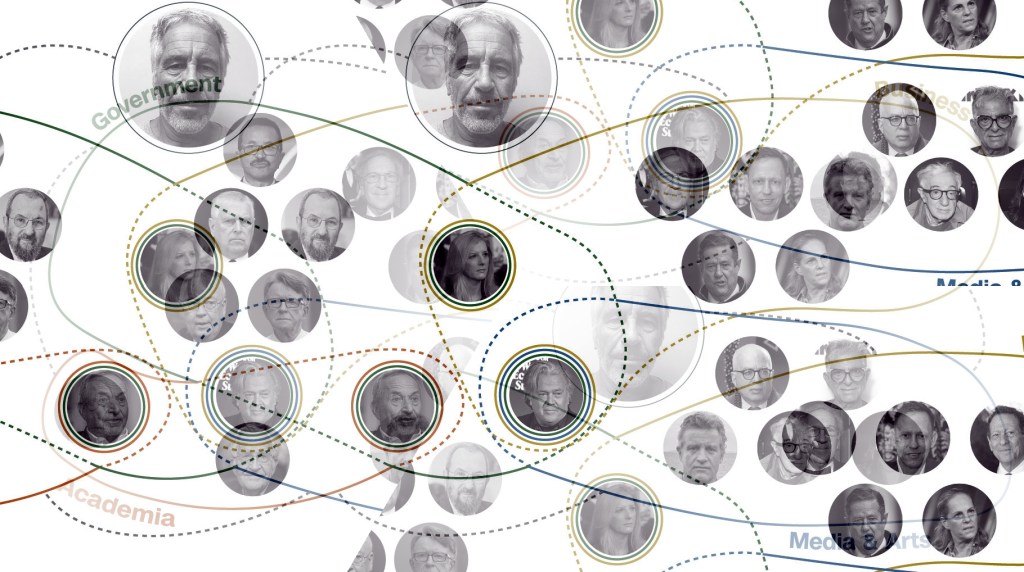

Life-forms are a natural universal means of recycling energy, death, entropy and of creating potentially useful and unique information. Intelligence, consciousness and other qualities of sentient and sapient life-forms are emergent properties of this continuing experiment with free energy. This interplay of energy and matter, through a process of cooperation and competition, gives rise to all the extraordinary biological complexity on Earth and all the knowledge and wisdom that humans have managed to achieve. All species must therefore have value as manifest useful engines.

The most problematic relative questions will always remain in assessing the value of our own and other species:

- What is the quantity of usefulness?

- How do we measure and value the utility?

- What is the ethical impact of competition for utilisation of resources?

Ultimately any system of valuation of different species and diversity must always be grounded in our lack of foresight about what the future holds for all life-forms – our Promethean limits.

Compossibility: The Thermodynamic Case for Diversity

If life is an engine that processes energy, then diversity is the ultimate optimisation of that engine. While simple computer algorithms often converge on a single “best” solution, natural evolution acts as a “machine for diversification,” continually accumulating different ways of being and solving problems.

This is the core of compossibility—the ability of different life forms and species to exist together to solve the complex problems of an unpredictable universe. A monoculture is thermodynamically fragile; it represents a limited number of ways to process the environment. In contrast, a diverse biosphere fills the ecological configuration space (the vast range of possible ways that life can be organised) with a variety of life-forms, each acting as a unique channel to disperse the cosmic fire of life.

The Ethics of Aliens

This moves us from physics to ethics. If we accept that life-forms are really useful engines, then wilfully destroying a species is not just a moral error; it is the destruction of a unique, functional solution to the problem of existence.

Consider the prospect of meeting an advanced alien civilisation. If we believe our current ethical framework—which often allows for the destruction of “lesser” species—is sufficient, we should be terrified. If aliens act toward us as we act toward other species, we will face extraordinary levels of human death, slavery and suffering.

It seems likely that any civilisation capable of surviving its own technology long enough to travel the stars must have developed an inter-species respect. They would understand that diversity is necessary to avoid self-destruction. They have likely already discovered what we’re only beginning to understand – that destroying unique biological algorithms is destroying irreplaceable solutions to existence itself.

To survive, we must adopt cosmic humility. We must not destroy species often even before we know what they do and how they do it – apart from anything because we cannot predict which biological algorithm will be essential for the future.

Does Time Stop for A Sufficiently Knowing Being?

Einstein’s Special Relativity teaches us that time is not absolute as it changes with speed. For any massive observer approaching light speed, the time along their path shrinks toward zero. If a photon could possess consciousness, it would not experience a journey over billions of light-years across the universe as taking any time at all. Instead, it would experience its source and destination (between a star and your eye) as a single, simultaneous event, with no ‘time’ taken in between.

Theories of entropy also point to another theoretical way to escape the feeling and flow of time; through infinite knowledge. For beings like us, the arrow of time is bound up with entropy – as correlations and uncertainty increase, we experience a one-way ‘unfolding’ of events. We see the future as open and the past as fixed because we have very limited information about the micro-states of the world.

If a being possessed “God mode”, i.e. complete knowledge of every particle in the universe (microstate certainty),27 the distinction between past and future would disappear. To such a being, the universe would not be a story unfolding but a static, four-dimensional sculpture (this is known as the ‘Block Universe’). In this structure, “now” is just a coordinate, no more special than “here.” The Big Bang and the universe’s pending Heat Death would simply be opposite edges of the same sculpture – both visible instantaneously at a glance. For this God like being, prediction is unnecessary because the future is not something that happens; it is something that is. The feeling of past, present and future would collapse into the ever present.

The Final Cycle

Ultimately, our role is to participate in this great flow of energy, information, and entropy. We are temporary vessels for a process much larger than ourselves. We are the flames, we carry the fire.

We might dream of achieving individual immortality through AI or medicine, but a moment’s reflection reveals this as an immature nightmare. A universe where nothing dies is a universe where nothing evolves, nothing learns, and nothing changes. It is a state of stagnation.

In the grand scheme of things, endless life for life-forms is the only true death.

“Murderers are easy to understand. But this:

that one can contain death, the whole of death,

even before life has begun,

can hold it to one’s heart gently,

and not refuse to go on living,

is inexpressible.”28

(Rainer Maria Rilke)

AI Podcast version:

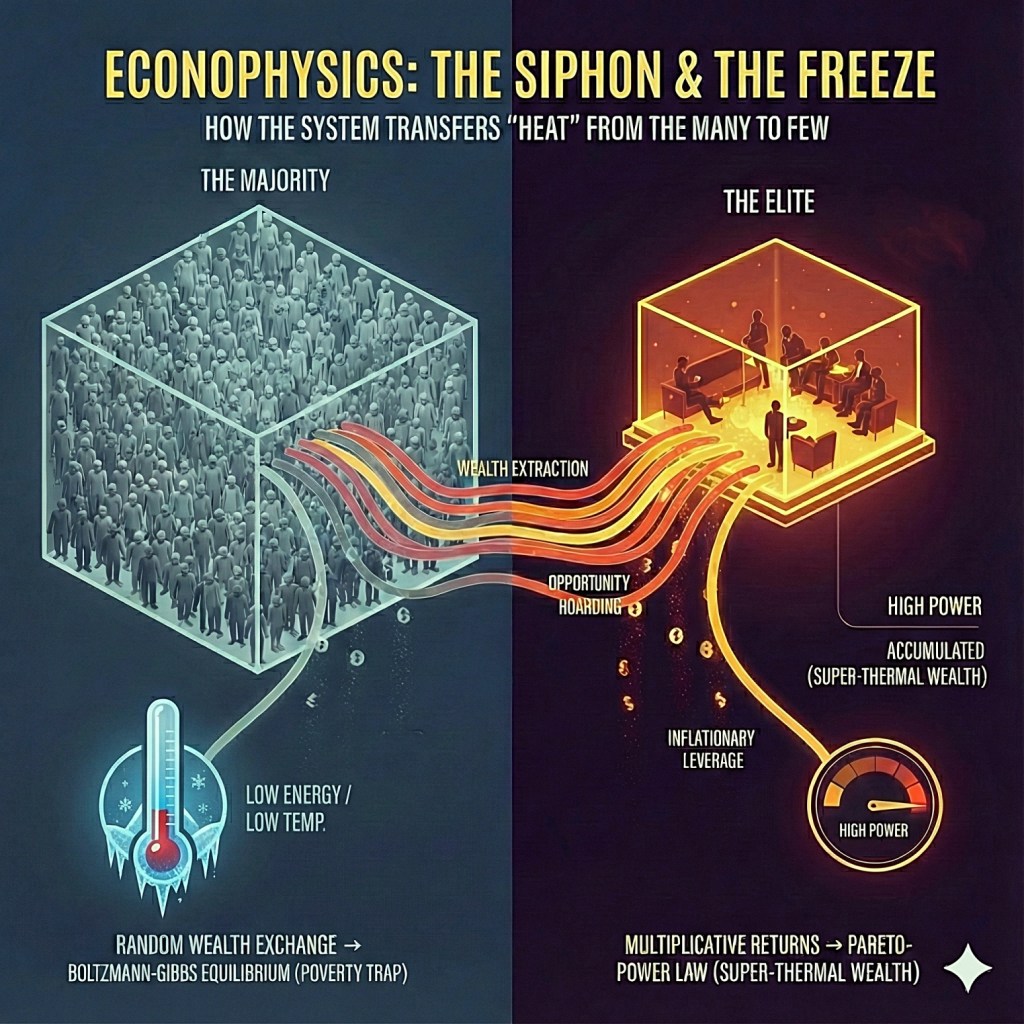

PS: If you would like to understand how the concept of entropy can be really useful in areas like economics (known as EconoPhysics), for example, to measure and manage inequality see:

Footnotes

- Charlotte Higgins, “There is no such thing as past or future”, The Guardian, 14 April 2018 – an interview with Carlo Rovelli. ↩︎

- It is therefore objective and invariant for all life-forms, though it may be intersubjective when looked at from the perspective of inanimate non-living matter and energy (if it has any perspective!). ↩︎

- Aparna Vidyasagar, “What Are Viruses?”, LiveScience, c. 2016. ↩︎

- Michael Le Page, “A Brief History of the Human Genome”, New Scientist, 12 September 2012. This sequence is a fragment of the 18S ribosomal RNA gene (specifically the human variant). This gene is highly conserved across all eukaryotes and is homologous to the 16S rRNA gene in bacteria and archaea. Because this genetic region is essential for life and changes very slowly, biologists use slight variations in its sequence to determine how closely related different species are on the Tree of Life. ↩︎

- “Natural Selection helps to select species which are most effective in survival and can efficiently utilize energy and negative entropy.”, Marek Roland-Mieszkowski, “Life on Earth: flow of Energy and Entropy”, Digital Recordings, 1994. ↩︎

- James Lovelock, Gaia: A new look at life on Earth, 1979. ↩︎

- Wikipedia, “Entropy and life”. We should however be very careful to be clearer about ways in which life-forms are low entropy structures and agents – with unusual agency and different from the surrounding (more random) environment – but also how they increase entropy in their surroundings. After all, life-forms appear to have arisen as the most efficient way to make use of free energy to speed up chemical equilibrium in the atmosphere. ↩︎

- What is life?, 1944. He later suggested “free energy” might be more precise than negative entropy. ↩︎

- Wikipedia, “The ultimate fate of the Universe”. ↩︎

- “Fern Hill”, Dylan Thomas, 1945. ↩︎

- Wikipedia, “Maxwell’s demon”. Image: Htkym, “Increasing Disorder”, Wikipedia, CC BY 2.5. ↩︎

- Quantifying Life, 2019. ↩︎

- Jordana Cepelewicz, “Mathematical Simplicity May Drive Evolution’s Speed”, Quanta Magazine, 29 November 2018. ↩︎

- “How Life (and Death) Spring From Disorder”, Quanta Magazine, 26 January 2017. ↩︎

- Christopher P. Kempes, David Wolpert, Zachary Cohen and Juan Pérez-Mercader, “The thermodynamic efficiency of computations made in cells across the range of life”, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, 2017. ↩︎

- Jordana Cepelewicz, “Mathematical Simplicity May Drive Evolution’s Speed”, Quanta Magazine, 29 November 2018. Image from the same source created by Lucy Reading-Ikkanda, fair use assertion. ↩︎

- Ibid. ↩︎

- What is Life?, 1995. ↩︎

- Santiago Hernández-Orozco, Narsis A. Kiani and Hector Zenil, “Algorithmically probable mutations reproduce aspects of evolution such as convergence rate, genetic memory, and modularity”, 2018. See also: Matheus Sant’ Ana Lima, “Algorithmic-Information Theory interpretation to the Traveling Salesman Problem”, 2019; Hector Zenil and James A. R. Marshall, “Ubiquity symposium: evolutionary computation and the processes of life some computational aspects of essential properties of evolution and life”, Ubiquity, 2013, pp. 1–16; Luís F. Seoane and Ricard V. Solé, “Information theory, predictability and the emergence of complex life”, Royal Society Open Science, 2018, 5(2): 10.31224/osf.io/gmzn5. ↩︎

- Wikipedia, “Algorithmically random sequence”. ↩︎

- “An algorithmic information theory of consciousness”, Neuroscience of Consciousness, Issue 1, nix019, 2017. ↩︎

- “the level of consciousness can be estimated from data generated by brains, by comparing its apparent and algorithmic complexities. Sequences with high apparent but low algorithmic complexity are extremely infrequent, and we may call them ‘rare sequences.’ Healthy, conscious brains should produce such data.” Ibid. ↩︎

- Justin K. Pugh, Lisa B. Soros and Kenneth O. Stanley, “Quality Diversity: A New Frontier for Evolutionary Computation”, Frontiers in Robotics and AI, July 2016. ↩︎

- Laura Getty and Kyounghye Kwon, “3.1: The Bhagavad Gita”, Humanities Libretexts, 18 May 2020. ↩︎

- Life is extraordinary but given the number of years the universe has been in existence (estimated at 14–15 billion) and the number of stars (estimated to be at least 1,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000), the likelihood that our star system is the only place with life seems low. On the other hand, maybe life is as rare as a beach spontaneously taking the shape of a sandcastle. All the more reason to take care of it. ↩︎

- Wikipedia, “Fermi paradox”. ↩︎

- An omniscient observer could know the entire quantum state of the universe (the full wavefunction or density matrix), that state itself already embodies certain fundamental irreducible uncertainties (such as Heisenberg uncertainty). The point is that there would be no subjective uncertainty for such a being. ↩︎

- “The Fourth Elegy”, Duino Elegies, 1923, trans. by Stephen Mitchell, Duino Elegies and the Sonnets to Orpheus, 2009. ↩︎

Leave a comment