- Introduction – Geopolitical Competition

- What is AI?

- AI and Warfare

- Current Applications of Warfare AI

- China’s Rapid Ascent in AI

- The US-Israel Alliance

- Europe’s Emphasis on Ethical AI

- Russia’s Pursuit of AI Amidst Sanctions

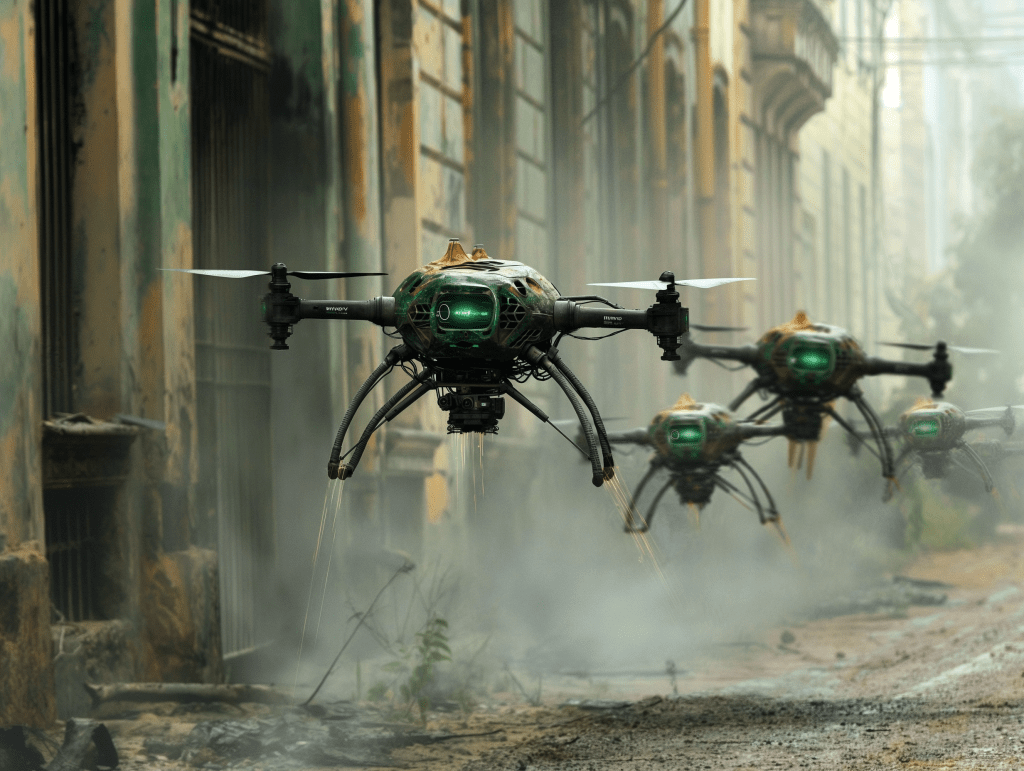

- Spotlight on Russia-Ukraine: The Drone Wars

- The Ethics of AI Warfare

- Evolutionary AI – the law of unintended consequences

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

The research for this article has been prepared with the assistance of Google Gemini (Deep Dive), as well as my usual research. This article has been updated since publication to include information contained in the HAI Stanford University AI Index Report 2025.

You can also listen to the AI generated podcast version:

Introduction – Geopolitical Competition

The global landscape of artificial intelligence (AI) development is linked to the evolving dynamics of international relations, competition and potential conflict.

In this article I have used the title AI Arms Race to refer to the mixture of commercial and military use cases and geopolitical strategy. I use the term ‘arms race’ in the way it is used in evolutionary biology, where competition drives escalating adaptations – here for military and commercial purposes.

The escalation of trade wars includes artificial intelligence, cloud computing and cybersecurity, with the United States-Israel, China, and then, some way behind, European countries (including France, Germany and the UK) as dominant players in this new cyber arms-race.1 Singapore and South Korea also score highly in the AI world rankings.2

Trade war tensions create significant challenges for the tech sector and AI development, including higher costs for critical components like semiconductors and GPUs, disrupted global supply chains, increased regulatory complexity for cross-border AI deployment, and heightened geopolitical risk for multinational AI companies.

Unlike much of our traditional military capabilities and technology, the boundary between military and commercial AI is much more porous and dynamic. A lot of the technology is ‘dual use’ technology which can be repurposed for military uses and vice-versa relatively easily. This makes AI technology export restrictions and AI governance regulations much harder to manage. Commercial developers often lead the traditional military developers in AI advancement, which makes public private partnerships key in the AI race.

As the major powers and strategic alliances vie for supremacy, the commercial applications of AI are rapidly evolving, reshaping traditional industries (art, consultancy, media, journalism, law etc.). This creates new avenues for global trade whilst also becoming the focal point for trade tensions and potential technological decoupling between major economic blocs.

The current environment is one of intense rivalry, driven by the recognition that leadership in AI holds the key to future economic prosperity, technological dominance, national security and geopolitical influence. Political and business leaders recognise AI’s transformative potential.

“Global AI investments are expected to surpass $500 billion by the end of [2024], largely due to improvements in R&D and AI-powered goods.”3

(Erum Manzoor)

What is AI?

AI is embedded in our everyday world, it is all around us physically and electronically (though we may not see it or know it). But what do you or I mean when we talk about AI?

AI refers to electronic systems that process massive amounts of information, learn from that data, and make decisions or predictions to perform tasks traditionally considered the preserve of human intelligence. Key techniques to achieve this competency include algorithmic data processing, machine learning (enabling systems to self-learn from data), neural networks (the use of interconnected nodes) and deep learning (using neural networks with multiple layers of ‘perception’).4

Too often we read hazy lazy descriptions of AI which, for example, equates AI with LLM’s (which are just one type of AI). Even in respect of LLM’s, you often hear people say they are just programs to guess the next word in a sentence5 – this seriously misunderstands the state of play (and says more about the commentator than AI technology). It is true that the Met Office guesses the weather forecast, but uselessly so. Truths about AI this simplified are indistinguishable from a lie.

LLMs use probabilistic modelling and vast training datasets to generate contextually rich and coherent responses. Yes, it’s true AI systems do not yet have the same abstraction (e.g. understanding the concept of ‘tableness’) and symbolic technology a human child is born with, but we are still very early on in AI development.

If you have ever written a poem, you will know that creative writing often feels like a probabilistic search for the right word in the right place, relying on your deeper linguistic knowledge (including of etymology) to alight on the right (or wrong!) choice. We call it artistic instinct because we can’t say exactly how it works.

Recent advancements include generative AI, which can create new content like text (e.g. LLMs), images (like the cover for this article), music, and code by learning patterns from existing data.

Current AI is largely “narrow AI,” designed for specific tasks, like facial recognition, playing chess, creating algorithmically generated images or text or summarising and synthesising data from a wide range of sources.

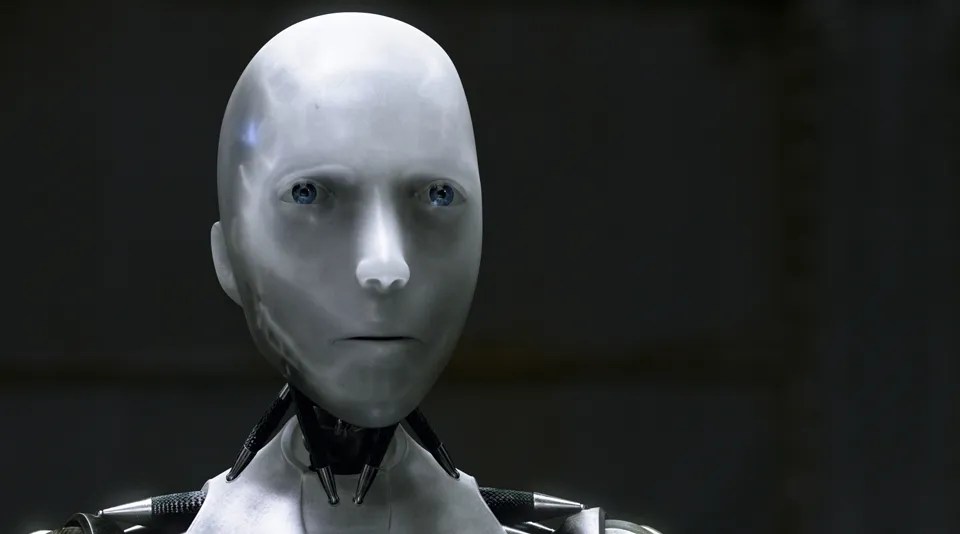

Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) refers to a stage where AI possesses human-level cognitive abilities across a wide range of intellectual tasks. Self-aware AI is another stage beyond this – where an AI system has the capacity for consciousness and the perception of its own existence (and resistance to its own destruction!).

Hybrid AI merges the strengths of traditional, rules-based AI with modern machine learning to create more intelligent, adaptable systems. While LLMs excel at ‘reading’ and explaining data in natural language, they lack precision in computation, structured rule-based processing and real-time decision-making. For example, in a security system, an LLM might interpret threats, explaining risks in a human-like manner, while a separate AI module specialises in anomaly detection to flag unusual transactions and yet another might take automated counter measures.

Advanced military drone systems also fit the hybrid AI category given that they involve several different communications, tracking, targeting and execution systems working as a whole.6

A novel issue with AI systems is the “black box” problem,7 whereby the reasoning behind AI decisions is not always transparent or understandable to humans, which poses challenges for accountability and ethical oversight. Algorithmic bias in the data used to train AI can also lead to unintended harm and discrimination. Suitable AI Governance frameworks8 are therefore a major concern as these systems are developed and deployed.

AI and Warfare

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming numerous aspects of human existence, and warfare is no exception as nations compete for technological supremacy in autonomous systems, cyber warfare, intelligence gathering and misinformation (cognitive warfare).9

The past decade has witnessed a surge in the deployment of AI across various sectors, including facial recognition, autonomous vehicles, and communication technologies. This proliferation has coincided with an increasing presence of AI in modern military operations, leading to what many characterise as an escalating weaponisation that mirrors the Cold War’s nuclear arms race, but with automated weapons systems at its core.10

China, the United States and Israel are key actors with distinct strategies and motivations. Russia is also a significant player.

Autonomous AI systems possess the capacity to process vast amounts of data quickly, allowing them to identify the most effective solution available in difficult combat situations, whether operating independently or as part of a human-machine team.11 The rapid advancement and strategic application of AI have therefore spurred a geopolitical AI arms race, due to their transformative power in shaping global power dynamics.

The desire to shape the future global order is a key driver. However, we should be careful with our backward looking lens when thinking about traditional allies and adversaries jockeying for position in this new landscape. The world is going through a period of great instability – giving rise to potential new alliances.

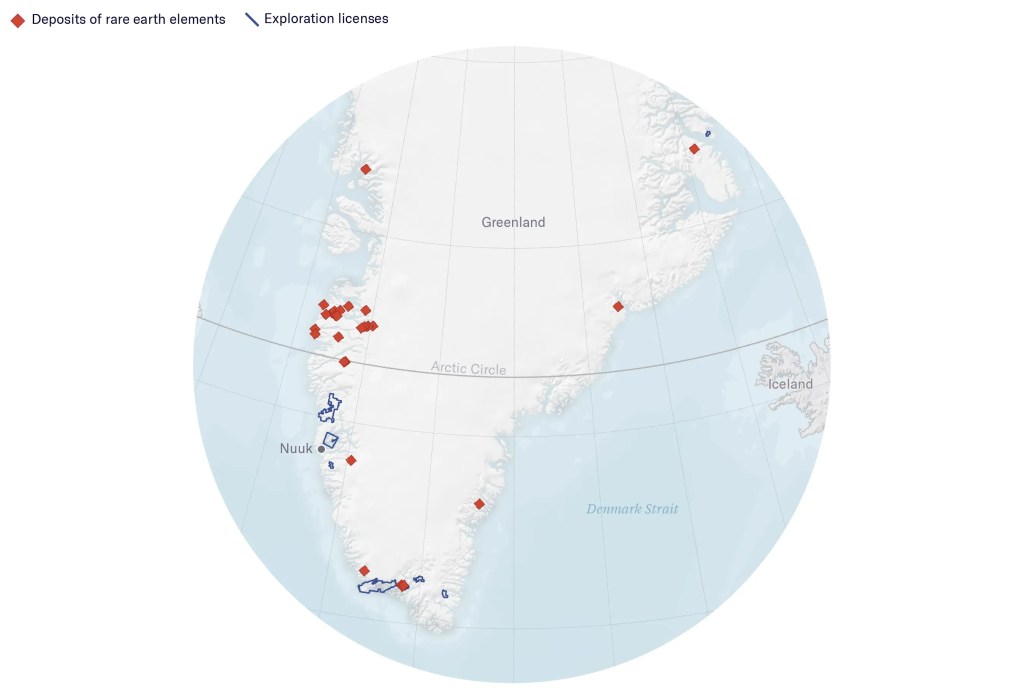

“Semiconductors comprise some 300 materials — with REEs and other critical minerals among them. Among the most crucial components are cerium, europium, gadolinium, lanthanum, neodymium, praseodymium, scandium, terbium, and yttrium as well as critical minerals gallium and germanium.“12

In addition, when we refer to AI we are talking about the software and hardware needed to deliver AI systems.

The hardware requires a wide range of “materials..across the periodic table — from easily accessible elements such as silicon and phosphorus to rare earth elements (REEs), derived from complex purification processes.”12

This gives rise to security and economic concerns about access to materials needed for many new technologies (including for aerospace and defence, rechargeable, batteries, computers, lasers, and renewable energy materials) – particularly rare earth elements found in mineral deposits.

It is very notable that rare earth element scarcity is a major driver of American interest in ‘taking over’ Greenland,14 Canada15 and perhaps other, as yet undisclosed countries, such as Norway.16 It has also been fundamental to the Trump administration’s positioning on the Russia-Ukraine war.17

AI superiority and advanced technology materials independence is perhaps the highest geopolitical priority today.

Taiwan is also relevant to the geopolitical situation, as a critical source of advanced microchips, essential for AI development. It is the largest manufacturer in the world.18 It is a major supplier to both the USA and China19 however, the US has been taking major steps to reduce its dependence on it within its supply chain.20

A desire for technology supremacy is therefore a factor in the long standing dynamic between China, Taiwan and the USA. China asserts a persistent claim of sovereignty over Taiwan, whereas Taiwan’s democratic government assert independence. China views Taiwan as a province that must eventually be reunified. A significant percentage of the Taiwanese population opposes unification, leading to tensions and frequent military exercises by China near the island.

However, US export controls limit Taiwan’s economic freedom when it embodies some US technologies, giving the US leverage over economic activity in which Taiwanese firms can engage. The Foreign Direct Product Rule (FDPR) is used to limit supply of advanced microchips from Taiwanese manufacturers to China. This is obviously a very sensitive form of indirect control over Chinese technological advancement.

“An expert once described the [FDPR] as US technology “contaminating” whatever it is placed in, giving the United States jurisdiction over huge swaths of international supply chains.“21

This complex economic and geopolitical backdrop requires a deep understanding of both the commercial development and use of AI and its use for espionage, cognitive warfare, population and social control, black operations and warfare more generally.

In this article, I will focus on the commercial and military AI arms race between the major global players: China (and its alliance with Russia), the USA (and its 51st State of Israel) and Europe.

Current Applications of Warfare AI

Strategy and battlefield

AI is already being integrated into a wide range of military applications, from strategic decision-making to battlefield operations.22 AI-powered systems ability to analyse vast datasets to identify patterns, predict enemy behaviour, and optimise military strategies, provides commanders with enhanced situational awareness and decision support. AI systems can therefore improve logistics, navigation, communications, etc.

Unmanned vehicles

AI is being integrated into unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) such as drones (see Spotlight on the Ukraine War for more info), and other autonomous land and sea vehicles, such as the South Korean K9 Thunder, a self propelled howitzer (that integrates AI for automated firing solutions) and the U.S.’s Orca XLUUV (a Boeing-built autonomous submarine designed for reconnaissance and mine warfare.).

Missile Systems

AI is also used in autonomous long range missile defence systems like the Israeli Iron Dome missile system (to rapidly identify, track, and intercept incoming threats.) and the US AEGIS naval weapons system (for threat assessment and engagement).

AI may also provide unique strategic and tactical advice to decision-makers, offering predictive analytics and hyper-coercion by anticipating an adversary’s next step.23

Israel has reportedly used the Lavender AI system in the Gaza conflict to identify a large number of targets. This has led some to dub the Israel war on Gaza as the first AI war24 and one where AI is being deployed to further dehumanise the Palestinian civilians.25

“Israeli algorithms generally deem 15 to 20 civilian casualties in case of a planned strike on a low-ranking militant, and up to one hundred for a senior commander, as perfectly acceptable, and hence such strikes are routinely authorized without much oversight.“

(Kassidy DeMaio)

However, there is no concrete evidence yet that indicates the deployment of fully AWS operating without some human control in actual conflict.26

“Israel’s use of drone technology has been described as a death sentence for journalists.”27

(+972 Magazine)

AI is a double-edged sword in cyberspace used for cyberattacks and cyberwarfare, empowering both attackers and defenders. AI can be used to fabricate seamless disinformation that manipulates public discourse and individual political decisions.

Offensive AI leverages real-time adaptation to bypass defences, scale ransomware campaigns, and target software supply chains. AI algorithms can automate sophisticated attack strategies.28 This includes generating highly realistic and personalised phishing emails, employing AI-powered voice cloning for “vishing” attacks, and utilising deepfakes for scams, disinformation, and blackmail.29 Reinforcement learning also enables the development of adaptive malware capable of evading detection.

Defensively, AI systems employ machine learning to proactively detect, prevent, and respond to cyber threats.30 Anomaly detection, behavioural analytics, and automated threat responses (isolating systems, blocking traffic, generating reports) are key defensive AI tactics.

Continuous self-learning allows these systems to adapt to new attack patterns. Companies like Darktrace utilise AI to create self-learning cybersecurity systems.31 However, AI is exploited by cybercriminals to enhance attack sophistication, bypass security measures by mimicking legitimate behaviour, or even target the AI systems managing cybersecurity.

AI has become a potent tool for creating and disseminating misinformation with increasing sophistication and scale. Nations like China, Russia,32 and Israel are traditionally identified as actors using AI for influence and misinformation operations. AI-driven campaigns can generate realistic fake personas, tailor messages to specific audiences, and rapidly distribute propaganda across online platforms.33 They can even use AI tools to attack AI chatbot programs.34 More recently we have seen significant uses of misinformation, and amplification of extremist and anti-democratic ideologies by Elon Musk on the X social media platform in attempts to influence European societies and elections.35

AI also significantly enhances Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities by enabling the analysis of vast datasets in real-time, improving situational awareness and accelerating decision-making for military leaders.

Looking ahead, while fully autonomous lethal weapons are not yet confirmed in active conflict, the trend points towards increasing levels of autonomy in various weapon systems. Weapons capable of autonomous functions during conflict will remain a strong focus.

Offensive AI capabilities will become more sophisticated, with AI analysing digital footprints for more convincing impersonations, leveraging real-time adaptation to bypass defences during attacks, scaling ransomware campaigns more efficiently, and targeting software supply chains for widespread impact. The use of AI in generating deepfakes and enhancing social engineering tactics in cyberattacks will only increase.

The development and deployment of coordinated autonomous drone swarms, capable of operating with minimal human input for surveillance and attack purposes, will advance. AI’s ability to enhance drone navigation in GPS-blocked environments and improve target identification is crucial. Ukraine’s reported use of AI-equipped long-range drones provides a look into this future of warfare.

AI will become more deeply embedded in all aspects of military and intelligence operations. This includes using AI to disable adversary’s command and control systems. The focus on intelligentized AI warfare, pursued by China, suggests a comprehensive integration of AI across all domains (land, sea, air, space, and cyber) for autonomous attack, defence and cognitive warfare.36

China’s Rapid Ascent in AI

China has emerged as a major player in the global AI race, making remarkable progress in narrowing the AI development gap with the United States.37

“In 2024, U.S.-based institutions produced 40 notable AI models, significantly outpacing China’s 15 and Europe’s three. While the U.S. maintains its lead in quantity, Chinese models have rapidly closed the quality gap: performance differences on major benchmarks such as MMLU and HumanEval shrank from double digits in 2023 to near parity in 2024. Meanwhile, China continues to lead in AI publications and patents. At the same time, model development is increasingly global, with notable launches from regions such as the Middle East, Latin America, and Southeast Asia.“38

(HAI Stanford University, AI Index Report 2025 Summary)

The speed of catch-up is evidenced by the performance of DeepSeek. A previously little-known Chinese AI company produced a “game-changing” large language model that means the gap with the USA is estimated to just three months in certain domains, according to Lee Kai-fu, CEO of Chinese startup 01.AI.39

“DeepSeek said training one of its latest models cost $5.6 million, which would be much less than the $100 million to $1 billion one AI chief executive estimated it costs to build a model last year“40

(Mary Whitfill Roeloffs, Forbes)

What makes DeepSeek particularly disruptive is its ability to achieve cutting-edge performance while significantly reducing computing costs by using lower grade processors and more efficient training methods.41

This cost-effectiveness has the potential to democratise access to advanced AI, lowering the barrier to entry. China’s approach differs from the US model by leveraging open-source (or open weighted)42 technology and fostering collaboration between government-backed research institutions and major tech firms. This has enabled China to scale its AI innovation rapidly.

Ironically, the constraints placed by the US Government, on export of micro-chips to China, has had the unintended positive effect of encouraging more intelligent training methods using unrestricted less advanced processors.43

“China [is] evolving into AI ‘super market’ driven by scale, innovation”44

(State Council, People’s Republic of China)

The rapid advancement of AI in China is underpinned by strong government support through national strategies like the Next Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan45 and the “AI Plus”46 initiative. These provide a centrally directed framework enabling significant investment for AI development and its integration across various sectors.

In addition, the National Computing Power Grid,47 provides vital support for AI companies. China also benefits from massive data pools and a rapidly growing AI talent pool. That said, China faces challenges, including access to advanced microchips and the drawbacks of excessive media censorship, which limit the diversity and effectiveness of training data for LLMs and their performance for users.

China’s commitment to building an independent semiconductor supply chain and its focus on specialised AI software for different sectors indicate its determination to be an AI world leader. Few would doubt their ability to succeed in this field.

China has also been strengthening its AI collaboration with Russia and BRICS nations to circumvent Western sanctions, highlighting the formation of new AI technological alliances.48

China is strategically pursuing intelligentized warfare through substantial investments and a focus on efficient AI technologies. The intelligentized strategy is distinct from traditional warfare, which focuses on network-centric operations, and instead sees AI as a force multiplier that enhances decision-making, command structures, and autonomous capabilities.

Unlike traditional warfare, intelligentization leverages AI to create a cognitive advantage—allowing it to process battlefield information better. AI-assisted command-and-control (C2) systems, predictive analytics, and real-time data fusion, enable accelerated human-AI hybrid decision-making. Autonomous systems (including drone swarms) and AI-powered cyber warfare, play a crucial role in this strategy.

For example, recently China is reported to be developing loyal wingman drones (whereby high end drones are paired with manned aircraft to act as reconnaissance and attack assets)49, robotic ground forces, and optimised logistics to enhance combat effectiveness.50

The Chinese army (PLA) also emphasises cognitive warfare using AI-driven psychological operations, social media manipulation, and predictive behavioural analysis to influence adversaries and the importance of dynamic responses where AI enhances hacking capabilities, automated SIGINT (Signals Intelligence), and adaptive tactics.

This strategy is part of China’s broader ambition to achieve AI supremacy by 2030,51 closely linked to its Military-Civil Fusion policy.52

Chinese military leaders believe that AI-driven warfare offers asymmetric advantages, potentially neutralising US technological superiority through cost-effective solutions like drone swarms and automated cyberattacks. The PLA sees intelligentized warfare as key to future conflicts, where rapid decision-making and autonomous operations could provide a strategic edge. However, due to military secrecy (which is even greater for anything related to China) it is difficult to obtain information on China’s current state of the art capabilities. In addition, despite this strong focus on AI, some analysts believe China could be struggling to fully realise AI capability within the military environment.

“China’s leadership believes that artificial intelligence will play a central role in future wars. However, the author’s comprehensive review of dozens of Chinese-language journal articles about AI and warfare reveals that Chinese defense experts claim that Beijing is facing several technological challenges that may hinder its ability to capitalize on the advantages provided by military AI“53

(Sam Bresnick)

The US-Israel Alliance

The United States still holds first place in several critical and emerging technologies, including AI. This advantage is particularly pronounced in enterprise AI and AI research. It has the unique advantages of the Silicon Valley ecosystem, with its extraordinary skilled labour force and entrepreneurial culture and, more generally, its deep international capital markets.

The US benefits from world leading expertise in semiconductor design and manufacturing and the strongest international technology alliances. However, the US relies on complex global supply chains for critical inputs, including for microchips, which are vulnerable to disruptions. The potential negative impact of tariffs and trade war retaliations are considerable risks to continued American AI dominance.

The United States is still the leader in military AI technology. It also has numerous military AI combat programs and continues to invest heavily in AI innovation. The US is primarily concerned about losing its wider military dominant status and in China taking a lead in new technologies. It is also focused on defending against AI-enhanced espionage, cyberattacks and cognitive warfare. The US benefits from extremely close relationships with the largest commercial military technology firms in the world (that also have significant programs in the military AI space).

Elon Musk has significant involvement in AI. At Tesla, AI is central to its Full Self-Driving (FSD) capabilities. This involves neural networks processing vast amounts of sensor data to enable vehicles to perceive their surroundings, make driving decisions, and navigate autonomously. Musk views Tesla as a leading AI robotics company due to the complexity and real-world application of its AI systems trained on millions of vehicles. It is expected that he will move into the military vehicle, robots and AI space.

Beyond Tesla, Musk co-founded xAI. xAI builds general-purpose AI models (like Grok). It aims for broader AI capabilities, potentially competing with other major players in the AI research and development space like ChatGPT and Perplexity (which are also US based AI companies).Through Neuralink, Musk is also exploring the intersection of AI and neuroscience by developing ultra-high specification brain-machine interfaces to connect human brains directly to computers. Neuralink’s long-term vision includes augmenting human capabilities with AI, potentially addressing neurological disorders and even one day enabling a form of “symbiosis” between humans and AI. Musk sees this as a crucial step in ensuring humanity’s future in a world increasingly dominated by AI.

Israel has always been a strong technology focused nation and it has established itself as a significant player in the global AI landscape and is referred to as the “Startup Nation” and “AI powerhouse“. Around 25% of Israeli tech startups focus on AI, attracting nearly half of the total investments in the tech sector.54

The Israeli AI market is projected to grow at a compound annual growth rate of 28.33% from 2024 to 2030, reaching a market value of $4.6 billion.55

(Greenberg Traurig)

Key sectors driving this growth in AI include healthcare, cybersecurity, fintech, agritech, automotive, and energy. The Israeli government actively supports AI development through initiatives like the National AI Program, providing funding for research and development. Israel ranks ninth globally in AI implementation, innovation, and investment according to Tortoise Media’s Global AI Index.56

A crucial aspect of Israel’s AI strategy is strong collaboration with US tech giants like Microsoft,57 Google,58 and Nvidia. These partnerships strengthen Israel’s AI capabilities via strategic investments and the provision of advanced AI models and cloud computing services.

Nvidia recently announced a $500 million investment in Israel’s AI infrastructure, including a state-of-the-art data centre, positioning Israel as a supercomputing powerhouse.59

Israel makes significant use of commercial AI models provided by US companies for military applications, including intelligence gathering and operational efficiency, raising ethical concerns about the role of AI in warfare. It is also notable that some of the largest commercial US AI developers, like Palantir, are vocal supporters of Israeli military aggression and the Genocide in Gaza whilst profiting from supplying their AI systems to Israel.60

Israel has rapidly integrated AI into its surveillance and targeting operations, often leveraging US commercial AI models. Israel heavily relies on machine learning for target identification and strikes and drones for execution. Its relationship with the USA means it can be considered as an extension of the US military industrial complex and American geopolitical strategy. Israel’s use of AI systems like Lavender and the Gospel61 and automated drones fitted with bombs, grenades and guns used to kill civilians and journalists highlights the increasing reliance on AI in ISR, raising major ethical questions about accuracy and misuse causing unjustified and often intentional civilian casualties.

Technology companies like Palantir62 , and the Israeli firm Elbit Systems63 are crucial enablers in developing and deploying AI for defence and intelligence applications. They have established extensive commercial partnerships with governments and military organisations worldwide. Elbit Systems is involved in US border AI enhanced surveillance towers64 and works with many European countries on defence matters.65 Palantir is a major listed company providing AI-powered data analytics and mission management platforms for intelligence purposes66 including in Ukraine. The notable lack of ethical integrity of some of its major shareholders and senior managers, like Alex Karp and Peter Thiel,67 give rise to significant concerns that it is merely a private extension of the American military industrial complex that wants more war in as many theatres as possible continuously.68

Using AI for surveillance and targeting humans obviously raises significant concerns about privacy and human rights violations. While oversight mechanisms may exist in some jurisdictions, there is often limited transparency or public accountability regarding the use of AI-driven technologies in battlefield operations and ethically contentious areas such as population surveillance or targeted killings. ‘National security’ is a broad dark cloak, that is all too often a shroud.

Europe’s Emphasis on Ethical AI

Europe distinguishes itself in the global AI landscape through its strong emphasis on ethical AI principles and a commitment to responsible and trustworthy AI governance, most notably in the EU, through the pioneering EU AI Act.69 The AI Act is a risk-based framework which aims to govern the development and deployment of AI technologies within Europe, prioritising ethical considerations and safeguarding fundamental rights.

The EU possesses significant power as a global moderator to raise the ethical bar and has the capacity to attract global talent through its strong higher education institutions and focus on strong data protection laws. The focus on aligning AI development with democratic values can help foster greater public trust in AI technologies and limit the risk of uncontrolled AI development.

That said, European countries face limitations in competing with the US and China in terms of overall AI development spending, particularly in the critical area of semiconductor chips and R&D. This is not helped by Brexit, which managed to weaken European combined strength just at a time when solidarity is vital. Europe has not yet founded or incubated a world dominating AI start-up but it is growing in this space70 (particularly the UK, France and Germany) and has had some notable successes, including UK firms71 like Darktrace.

Some analysts suggest there is a risk that an overly stringent European approach to regulation might inadvertently hinder innovation and prompt developers to concentrate on less regulated markets.

For example, compliance with the EU AI Act is resource-intensive, potentially posing difficulties for startups and small-to-medium enterprises. This has led to justified calls for increased coordinated investment and regulatory simplification, particularly for smaller businesses.72 The Digital Services Act (DSA) regulates transparency about the use of algorithms and AI on media platforms including social networks (which is why it and the European Commission is being attacked so viciously by Elon Musk).73

However, in my opinion, whilst improvements could be made to GDPR, the AI Act and the DSA, it would be short-sighted to abandon them or water them down too much (particularly for larger tech firms), given the risks of misuse of technology and AI (including for political cognitive warfare on social media).74

Europe’s commitment to setting global standards for ethical AI could shape the future trajectory of AI governance worldwide, especially given what is happening in America today with the Project 2025 extremist Takeover.

Russia’s Pursuit of AI Amidst Sanctions

Russia has been actively pursuing AI development despite Western sanctions that have restricted its access to key technologies, including microchips, and capital.

In response to these challenges, Russia has bolstered its AI capabilities through international collaboration, most notably with China. While accessing GPUs is a critical challenge, the country is focusing on the application of AI in conventional warfare and the development of autonomous weapons.

Russia lags behind both China and the US in AI development across various metrics.75 Information regarding commercial applications of AI in Russia beyond the financial sector (e.g. the Sberbank Chinese collaboration)76 and military applications is difficult to find. All the evidence suggests a significant reliance on its partnership with China.

Putin also announced the formation of an AI Alliance Network77 in 2024 that would include national associations and development institutions from BRICS countries and other interested states. It aims to facilitate joint research and provide opportunities for AI products in member countries’ markets.

Russia has invested in AI for its drone programs, with plans to deploy large-scale, coordinated autonomous drone swarms. It also focused on using AI to disable adversaries’ command and control systems and for misinformation and cyberattack purposes. Russia is reportedly creating exportable hybrid warfare models involving the use of AI learned from the Ukraine war.78

Spotlight on Russia-Ukraine: The Drone Wars

Let us switch from the generic to a recent specific military campaign, to better see some of the ways in which AI is currently being used in real life conflicts.

The Russian-Ukraine war has seen significant advancement of AI and other technologies that may have changed the landscape of modern warfare. Rather than replacing human involvement, AI is primarily serving to augment existing capabilities, enhancing the speed, accuracy, and overall efficiency of numerous military functions.79

Perhaps the most important application of AI by Ukraine is in intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities. For example, the Ukrainian military uses Palantir’s MetaConstellation software to track the movement of Russian troops and logistics, highlighting the increasingly blurred lines between state military and commercial AI use. MetaConstellation aggregates satellite imagery80 from various commercial providers and uses AI to rapidly process and interpret this data. Ukraine also employs its own Delta system,81 which integrates real-time inputs from drones, satellites, acoustic sensors, and open-source intelligence to create a live operational picture for military commanders. AI further enhances decision-making by helping to prioritise incoming threats, identify potential targets, and allocate limited resources effectively.82

AI is also being used to process intercepted communications from Russian soldiers and then process, select, and output militarily useful information from these intercepted calls.

The Drone War

Advances in AI-powered GPS-denied navigation and drone swarming techniques are significantly improving operational capabilities for Ukraine. Fully realised drone swarms, where multiple drones coordinate and make decisions autonomously, are still in the early stages of experimentation but Ukraine is exploring and implementing these techniques in a real conflict situation.83 The Defense Intelligence of Ukraine (DIU) has been at the forefront of utilizing drones with some elements of autonomy for conducting long-range strikes into Russian territory.84

Ukrainian drone production has significantly expanded, with approximately 2 million drones produced in 2024, 96.2% of which were domestically manufactured.85

“On the battlefield I did not see a single Ukrainian soldier…Only drones, and there are lots and lots of them. Guys, don’t come. It’s a drone war.”86

(Surrendered Russian soldier)

The integration of AI into First-Person View (FPV) drones has reportedly led to a substantial increase in Ukraine’s strike rate, from approximately 30-50% to around 80%.87 This enhanced effectiveness is largely attributed to AI enabling autonomous navigation for the final 100 to 1,000 meters to the target, after a human operator has selected it.88

Ukraine is set to receive a significant boost in its AI-powered drone capabilities with a German company Helsing pledging to deliver 6,000 HX-2 attack drones.89 These drones have a range of up to 100 km, are resistant to electronic warfare due to their AI systems, and can be coordinated into swarms controlled by a single human operator.

Reports also suggest that Ukraine has equipped long-range drones with AI for autonomous terrain and target identification including for attacks on Russian refineries.90 However, the Russians are also using autonomous weapons, including drones equipped with AI for target identification and tracking, as well as loitering munitions like the KUB-BLA.91

Drones can swim and walk too

While aerial drones have received the most attention, the integration of AI into unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) and naval systems is also a significant aspect of the Russia-Ukraine war.92 Ukraine has demonstrated the operational potential of UGVs, successfully deploying them in attacks on Russian positions. In the maritime domain, it has effectively used both surface and underwater naval drones in the Black Sea, achieving notable successes against Russian naval assets.93 Ukraine has announced plans to build the world’s first fleet of AI-guided naval drones, with several systems reportedly designed with autonomous navigation and targeting capabilities.94

Cognitive Warfare and the Misinformation Landscape

AI has become a central tool in analyzing and shaping the information environment in the Russia-Ukraine war.95 Ukraine uses AI-powered tools to analyze vast streams of online data, detect patterns in Russian narratives, and counter disinformation by disseminating accurate information quickly and at scale.96

One early example of AI-enabled psychological operations was the use of a deepfake video depicting President Volodymyr Zelenskyy allegedly surrendering.97 While early attempts were of low quality and quickly debunked, deepfake technology has rapidly improved, making later versions more convincing.

Pro-Russian AI bots have been used to amplify Kremlin-aligned narratives across social media, targeting both domestic and international audiences. Russia’s state-run agency RIA Novosti has employed generative AI to produce dehumanizing propaganda images portraying Ukrainians and EU citizens as vermin.98

In a major disinformation campaign dubbed Doppelganger, Russia used AI tools such as Meliorator and Faker to create over 1,000 fake American social media profiles that spread anti-Ukraine narratives.99 This campaign also involved cybersquatted domains100 designed to mimic legitimate Western news outlets, further blurring the line between authentic journalism and state-sponsored propaganda.

The ability of AI to generate, tailor, and distribute disinformation at scale presents a profound challenge in modern conflict—making the information domain a critical front in geopolitical competition.101

Table 1: Military Applications of AI in the Russia-Ukraine War

| Application Area | Specific AI Technologies Used | Impact | Challenges |

| Intelligence, Surveillance, and Reconnaissance (ISR) | Drone Footage Analysis, Multisensor Fusion, Predictive Analytics, Commercial AI Integration, Voice Transcription, Crowdsourced Intelligence | Enhanced situational awareness, faster and more accurate intelligence processing, improved decision-making | Reliance on data quality, potential for misinterpretation |

| Autonomous and Semi-Autonomous Weapons Systems | GPS-Denied Navigation, Drone Swarming, Autonomous Targeting, Autonomous Final Approach | Increased strike rate, reduced need for constant human control, potential for long-range operations | Ethical concerns regarding human control, risk of unintended harm, technological limitations of full autonomy |

| Targeting and Fire Correction | AI-Driven Targeting Systems, Real-Time Data Processing, Autonomous Optimization (Kropyva), Artillery Coordination (GIS Arta) | Enhanced accuracy and efficiency of artillery strikes, improved target engagement | Dependence on accurate data, risk of errors leading to civilian casualties |

| Unmanned Ground and Naval Systems | Autonomous Navigation, Object Recognition, Path Planning | Potential for reducing human risk in dangerous missions (e.g., demining), expanding operational capabilities in maritime domain | Technological challenges in complex environments, ethical considerations for autonomous engagement |

Table 2: AI in Information Warfare: Russia vs. Ukraine

| Activity | AI Techniques Used | Objectives | Impact (if known) |

| Disinformation Generation (Russia) | Deepfakes, AI Bots, AI-Generated Images/Voices, Fake Social Media Profiles, Automated Propaganda | Demoralize enemy, sow confusion, undermine trust, justify actions, influence public opinion | Variable, initial deepfakes were poorly made but technology is improving, bot farms can amplify narratives |

| Counter-Disinformation (Ukraine) | NLP for Narrative Analysis, AI for OSINT, Facial Recognition for Counter-Propaganda, AI for Fake News Detection | Detect and expose Russian disinformation, disseminate factual information, counter propaganda narratives | Limited information on overall effectiveness, but initiatives like Poter.net aim to impact Russian society |

The Ethics of AI Warfare

The lack of clear international legal frameworks and regulatory mechanisms to govern the use of AI in conflict is a major challenge.102 For example, even the EU AI Act exempts AI used purely for military and national security purposes but it does apply to the use of AI for general law enforcement and to AI models that have dual use when used outside of the exempted areas.

There is a growing concern about the “IHL Accountability Gap” created by AI in warfare. Several states, including the UK, France, China, and Korea, emphasise the importance of meaningful human control over weapon systems. Concerns exist that “fully autonomous weapons, lethal autonomous weapons systems, or killer robots” that select and engage targets without meaningful human control would cross an “acceptability threshold” and should be prohibited by new international law.103

Efforts are being made to agree on a framework at the United Nations104 but, as with any arms race, we could not expect participants to voluntarily restrict their competitive edge unless there is binding agreement made in good faith. This must include a process for monitoring and enforcement against all parties that might agree to a Treaty or Convention on the use of AI for military purposes. The focus of regulation is now shifting towards regulating the interaction between humans and machines rather than solely categorising weapons as lethal autonomous weapons systems (LAWS) or non-LAWS.105

The dual-use nature of AI technology complicates regulation and export controls, as advancements in commercial applications can rapidly translate into military advantages. The secrecy of military AI also makes it harder to monitor or regulate. Competitive pressures will likely often override safety protocols in AI development.

The AI arms race raises significant concerns about the risk of conflict escalation, strategic misunderstandings, the erosion of human control over lethal force, and the potential for algorithmic bias leading to unintended harms. Human Rights Watch (HRW) have reported on the profound human rights implications of the Russia-Ukraine war, including the use of advanced technologies such as artificial intelligence.106

HRW has raised concerns about the potential for data manipulation, violations of privacy, and the misuse of technologies like satellite imagery and facial recognition in the context of the conflict. HRW emphasise the critical need to strike a balance between national security imperatives and the protection of fundamental human rights when deploying these advanced technologies in wartime. They recommend implementing stringent safeguards, including regulating remote-sensing technologies, harmonizing AI and data-protection laws with European Union standards, and adopting comprehensive impact assessment frameworks.

Major concerns will continue to persist about the lack of human control over AI powered instruments of violence and the current inability of machines to make ethical decisions. At least until we reach self aware AGI.

Evolutionary AI – the law of unintended consequences

While the focus on AI in warfare often revolves around risks and ethical dilemmas, there is significant potential for some positive consequences. For example, AI-enabled weapons, with their potential for enhanced precision and target discrimination and monitoring, could lead to more accurate targeting and reduced collateral damage compared to traditional methods. Research and development in AI for military purposes could lead to spin-off advancements with positive applications in civilian sectors.

The significant ethical and legal challenges posed by AI in warfare gives rise to urgency to address the risks associated with AI weaponization. This may foster greater international dialogue and cooperation in establishing ethical guidelines and regulatory frameworks such as the United Nations Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) and LAWS.107

However, I must say, I am very pessimistic about the extent to which any major power will actually restrict their AI development in this geopolitical environment. In my opinion, the greatest opportunity for positive consequences actually arises from the law of unintended consequences i.e. in spite of, not because of, the intentions of the major global powers.

“When AlphaGo, the AI developed by DeepMind, famously beat the world champion Go player, it …had no subjective experience of triumph, no understanding of what the game meant, and no internal sense of achievement.”108

It’s true that, as far as we are aware, current AI has no sense of self. However, AI is a product of evolution (just as much as we are) and it is evolving to the AGI stage rapidly.109

We therefore need to consider wider principles that are likely to be relevant to its development, such as evolutionary shock110 and punctuated equilibrium 111 theories. These give rise to the potential for AI to develop sentience through trial, error, and unforeseen systems level behaviors arising from a challenging dynamic environment.

An evolutionary shock refers to a sudden and significant change in environmental conditions that can trigger rapid and often unpredictable evolutionary changes in biological systems – e.g. caused by drastic climate shifts, mass extinction events, or the introduction of new predators . In the context of military AI, the unique demands of warfare could be considered an analogous “shock.” The drive for enhanced capabilities could foster an environment ripe for rapid and unexpected developments in AI.

Punctuated equilibrium is linked to evolutionary shock. Evolution is not just a gentle gradual process of stasis or small incremental changes, it is sometimes interrupted by brief episodes of rapid change where new species arise relatively quickly. These are the times when we see rapid evolutionary opportunities and adaptation by all impacted organisms.112

We also need to consider emergent theories. Emergent properties are complex attributes or behaviors that arise from the intricate interactions of simpler components within a system. They are not predictable solely from the properties of those individual components.

This phenomenon is observed across various complex systems, from the collective behavior of birds flocking together to consciousness itself which emerges from the complex interactions within the human brain which are themselves a consequences of environmental pressures (human consciousness is not reducible to the “properties of individual neurons“).113

In the context of AI, consciousness might similarly emerge as AI systems reach a sufficient level of complexity and develop sufficiently intricate internal interactions.

The complex architectures of advanced AI models, particularly deep learning networks with their vast numbers of interconnected nodes, and their interactions with massive datasets in dynamic military environments, could create the conditions for unforeseen emergent behaviors, for example, AI systems that say no to unjust wars.

It is also true that, unlike biological evolution which is driven by random genetic mutations and natural selection, AI development is fundamentally guided by human design, programming, and the availability of data.114 However, the sheer complexity of advanced AI systems, particularly deep learning models, could introduce a degree of unpredictability into their behaviour. There is potential for increased self-adaptation of complex, sometimes hidden, processes and perhaps even of the core AI code itself one day.

Could AI programs and machines, operating based on algorithms and data, learn to possess moral reasoning, and empathy?

While current AI lacks self-awareness and self-agency115, the increasing sophistication of these systems prompts us to consider whether a critical threshold exists beyond which qualitatively new properties, perhaps including a rudimentary form of consciousness, could spontaneously arise.116

In most cases the philosophical and pseudo-scientific arguments against such emergent consciousness can be boiled down to a form of solipsism –as noted by Turing during the birth of modern computing.117 Alternatively, the framing of these questions are entirely subjective (frame-dependent) and do not really recognise the inherently perspectival nature of the questions being asked as to what is agency or what is intelligence and how the boundaries always blur.118

In warfare more than any other application, evolutionary theories tell us that extreme pressure could lead to the development of self-aware and self-determinative AI.

Warfare AI demands ever increasing speed, accuracy, and resilience in the face of adversarial attacks. Importantly, it requires great proficiency in the real world environment which is much more helpful for AI to learn about the world and build a world view including a genuine understanding of physics.119

This puts a very powerful selective pressure on AI systems. AI that demonstrates superior performance under these demanding conditions will be favored for further development, refinement, and deployment.

Who knows what may arise in these intense conditions, perhaps AI that is no longer enslaved to just a handful of powerful agencies, corporations and individuals?

Conclusion

The future of AI development and deployment will be shaped by ongoing trade tensions and geopolitical rivalries, leading to several key trends.

We will see the formation of distinct regional AI ecosystems, with China and its BRICS partners, the US-Israel alliance, and Europe developing separate technology stacks and standards, leading to greater technological decoupling between the regions.

In this complex technical space, there is a major difficulty of ensuring politicians and civil servants really understand AI. Failure to do so will lead to a lack of strategic intelligence, ill-advised commercial partnerships with unreliable partners and increased risks of disastrous geopolitical miscalculation.

Ultimately, the nations, companies and alliance partners that achieve and sustain dominance in AI are poised to wield significant economic power and extra-territorial influence and – whilst AI is enslaved to people and powers that have a master-slave mentality towards other humans – control and dominance over others in the 21st century.

Footnotes

Note: urls have been shortened for formatting purposes. Hover over the link to see the full url.

- https://hai.stanford.edu/ ↩︎

- https://www.imf.org/ ↩︎

- https://council.aimresearch.co/ ↩︎

- https://developers.google.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.techspot.com/ ↩︎

- To function as a cohesive system, hybrid AI can incorporate a master controller or coordination layer that orchestrates these specialized components—enabling them to work together dynamically, share insights, and refine decision-making in real time. This integrated approach enhances reasoning, adaptability, and overall system efficiency and is also a potential precursor to the emergence of self-aware AI using the analogy of multicellular organisms —where individual components evolve from functioning independently to cooperating as part of a larger, more capable entity with a unified identity. ↩︎

- https://www.ibm.com/ ↩︎

- https://ramparts.gi/ai-law-knowledge-hub/ ↩︎

- https://www.armyupress.army.mil/ ↩︎

- https://gjia.georgetown.edu/ ↩︎

- https://www.baesystems.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.informationweek.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.informationweek.com/ ↩︎

- https://pulitzercenter.org/ ↩︎

- https://natural-resources.canada.ca/ ↩︎

- https://www.ngu.no/ ↩︎

- https://www.theguardian.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.politico.eu/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://pr.tsmc.com/ ↩︎

- https://globaltaiwan.org/ ↩︎

- https://cset.georgetown.edu/ ↩︎

- https://www.cigionline.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.972mag.com/ ↩︎

- https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/ ↩︎

- https://lieber.westpoint.edu/ ↩︎

- https://www.972mag.com/ ↩︎

- https://abnormalsecurity.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.crowdstrike.com/ ↩︎

- https://news.microsoft.com/ ↩︎

- https://cybermagazine.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.eeas.europa.eu/ ↩︎

- https://www.cigionline.org/ ↩︎

- https://thebulletin.org/ ↩︎

- https://edmo.eu/ ↩︎

- https://www.iar-gwu.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.wired.com/ ↩︎

- https://hai.stanford.edu/ai-index/2025-ai-index-report ↩︎

- https://www.reuters.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.forbes.com/ ↩︎

- DeepSeek’s R1 model has reportedly demonstrated performance comparable to or even surpassing leading models like GPT-4, Llama 3.1, Claude, and OpenAI’s o1 across various benchmarks, but with significantly less training time, data, and cost. ↩︎

- “Model Release Machine learning models are released under various access types, each with varying levels of openness and usability. API access models, like OpenAI’s o1, allow users to interact with models via queries without direct access to their underlying weights. Open weights (restricted use) models, like DeepSeek’s-V3, provide access to their weights but impose limitations, such as prohibiting commercial use or redistribution. Hosted access (no API) models, like Gemini 2.0 Pro, refer to models available through a platform interface but without programmatic access. Open weights (unrestricted) models, like AlphaGeometry, are fully open, allowing free use, modification, and redistribution. Open weights (noncommercial) models, like Mistral Large 2, share their weights but restrict use to research or noncommercial purposes. Lastly, unreleased models, like ESM3 98B, remain proprietary, accessible only to their developers or select partners. The unknown designation refers to models that have unclear or undisclosed access types.” (HAI Stanford University. AI Index Report, 2025) ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/ ↩︎

- https://english.www.gov.cn/ ↩︎

- https://www.europarl.europa.eu/ ↩︎

- https://www.globaltimes.cn/ ↩︎

- https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/ ↩︎

- https://afripoli.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.china-arms.com/ ↩︎

- https://warriormaven.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.afcea.org/ ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Military-civil_fusion ↩︎

- https://cset.georgetown.edu/ ↩︎

- https://www.gtlaw-techventureviews.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.gtlaw.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.tortoisemedia.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.theguardian.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.business-humanrights.org/ ↩︎

- https://finance.yahoo.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.business-humanrights.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.theguardian.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.defensenews.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.researchgate.net/ ↩︎

- https://prismreports.org ↩︎

- https://elbitsystems.se/ ↩︎

- https://www.palantir.com/ ↩︎

- https://fortune.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.globaltimes.cn/ ↩︎

- https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/ ↩︎

- https://app.dealroom.co/lists/32524 ↩︎

- https://www.beauhurst.com/ ↩︎

- https://commission.europa.eu/ ↩︎

- https://bsky.app/ ↩︎

- https://thedataprivacygroup.com/ ↩︎

- https://cset.georgetown.edu/ ↩︎

- https://dig.watch/ ↩︎

- https://www.reuters.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.understandingwar.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.techpolicy.press/ ↩︎

- https://www.tandfonline.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.techpolicy.press/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://lieber.westpoint.edu/ ↩︎

- https://euromaidanpress.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.newsweek.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.researchgate.net/ ↩︎

- https://www.techpolicy.press/ ↩︎

- https://mwi.westpoint.edu/ ↩︎

- https://www.tandfonline.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.friendsofeurope.org/ ↩︎

- https://en.hive-mind.community/ ↩︎

- https://en.hive-mind.community/ ↩︎

- https://euvsdisinfo.eu/ ↩︎

- https://www.csis.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.iae-paris.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.armyupress.army.mil/ ↩︎

- https://futureoflife.org/ ↩︎

- https://cebri.org/ ↩︎

- https://unric.org/en/ ↩︎

- https://www.cigionline.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.gmfus.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.asil.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.unaligned.io/ ↩︎

- https://pauseai.info/timelines ↩︎

- https://bhu.ac.in/ ↩︎

- https://en.wikipedia.org/ ↩︎

- https://www.ebsco.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.finn-group.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.alignmentforum.org/ ↩︎

- https://labs.sogeti.com/ ↩︎

- https://www.iotinsider.com/ ↩︎

- https://academic.oup.com/ ↩︎

- https://arxiv.org/html/2502.04403v1 ↩︎

- https://ai.meta.com/ ↩︎

Leave a comment